It's time to emit how little we know

Why a modest amount of carbon literacy is key to quashing the climate crisis

Hi! I’m Sarah. Minimum Viable Planet is my weeklyish newsletter about climateish stuff, and how to keep it together in a world gone mad. I’m always curious to know what you think. If you like this newsletter, please subscribe.

This week’s edition is an opinion piece I wrote for Yes! Mag on climate literacy. There’s a double whammy of injustice when you think about the fact that the burden of solving climate has been unduly shunted to individuals, who are then deprived of the information necessary to do what they’re being told to do. I got to interview two excellent academics who work on climate at the intersection of psychology, engineering, and behavioural science. They’re worth checking out: Jiaying Zhao, Shahzeen Attari.

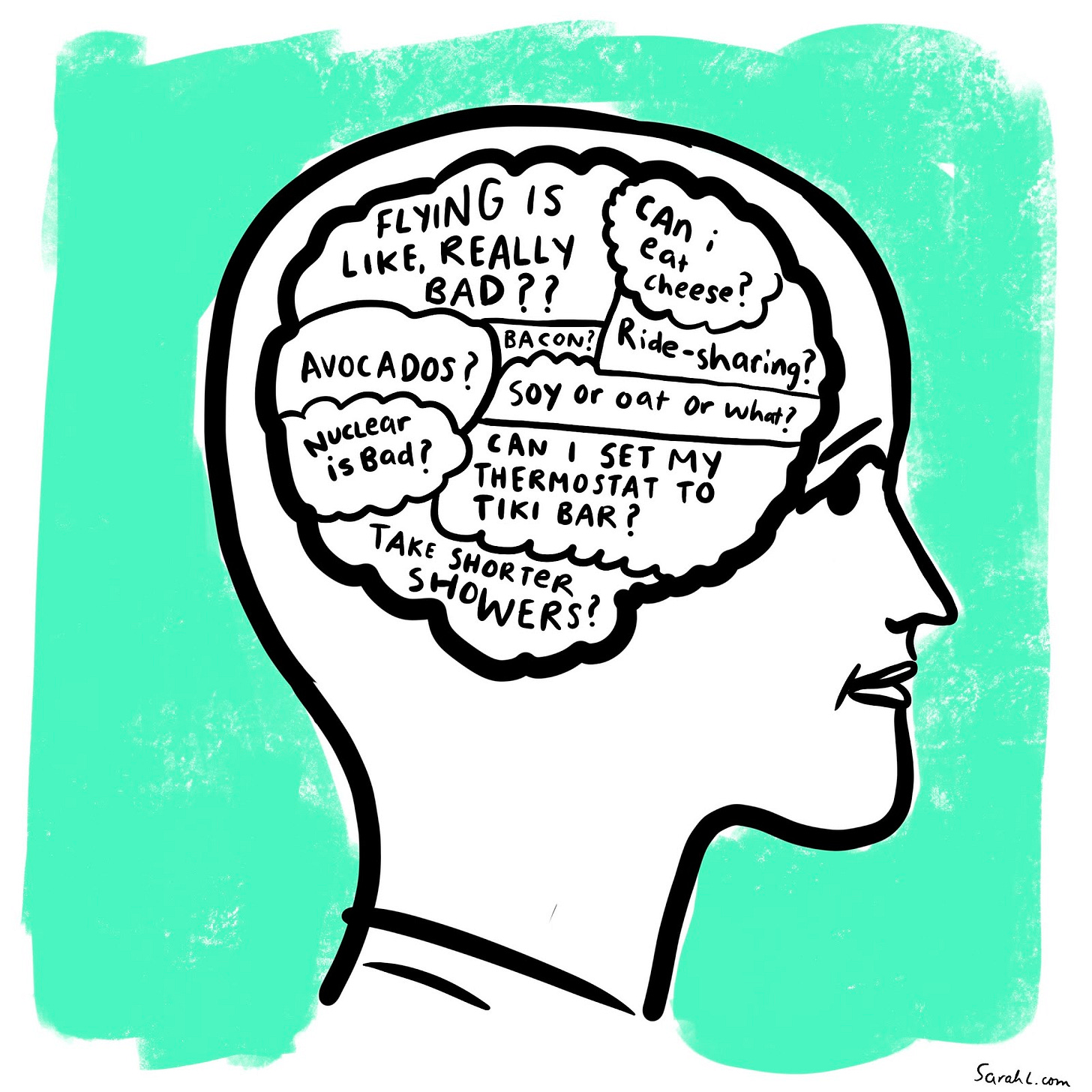

We know less than we think we know about climate. And we know even less than that about our carbon footprint. This doesn’t mean we’re all idiots. Instead, it means that we live in a world where this information isn’t widely available, or particularly well-conveyed. This needs to change. Very quickly.

We don’t need everyone to become carbon-computing experts, but we do need to make it easier to understand the basics of climate science and emissions reductions, in the hopes that people will be empowered and inspired to take climate action.

What We Don’t Know

The fancy term for thinking we know more than we do is overconfidence bias. In the case of climate, a new VICE study finds we overestimate our knowledge significantly. The study revealed that “67 percent of adults around the world said they had a good understanding of climate change terms, but when asked to choose the best definition of those terms, only 41 percent of adults chose answers that showed they knew what they were talking about.” It seems our knowledge of basic climate change is, well, not so hot.

Which is why it’s no surprise that a new University of British Columbia study finds that North Americans also don’t know much about what causes emissions. In fact, we are surprisingly off the mark when asked to make trade-offs (nope, the emissions from a transatlantic flight cannot be mitigated by picking up litter). Carbon numeracy, or people’s knowledge of the carbon impacts of goods and services, is a remarkably under-researched area, so the good news is that we’re starting to learn about how much we don’t know. “People have very incorrect ideas of what’s effective and what’s not,” says Jiaying Zhao, an associate professor of psychology at UBC, and one of the study’s co-authors.

Why We Don’t Know

There are lots of reasons why we don’t know nearly enough about climate change and carbon emissions. The consensus on climate science grows ever stronger by the day, but has only existed for a few generations, and is still highly politicized. And the science is complicated, especially when we’re not formally taught about climate change with any great breadth or consistency across our formal education.

In some areas, the public has been well educated, as is the case with the benefits of electric vehicles versus gas vehicles. In other areas we’ve been fed a lot of misinformation, such as the overstated benefits of recycling that have minimal effect on our emissions reductions.

What’s more, numbers are communicated in ways that have no relevance to the average individual who doesn't talk in megatonnes. Better to say that a transatlantic flight is equivalent to about the same amount of emissions that an average person in The Global North produces in an entire year.

Another key reason all this is so difficult is that it’s impossible to know the carbon footprint of most of the stuff we buy. Climate impacts are much more complicated than calories or personal finances, as they require understanding of energy, agriculture, and fuel efficiency. Plus, corporations, many of whom are responsible for huge amounts of global emissions, have a vested interest in obfuscating the role their products have played in the warming of the planet.

Why It Matters

All of this is so important because you can’t measure what you don’t understand. It’s hard to care about climate and know what actions to take or advocate for if we don’t know what emissions are or what we can do about them.

What We Can Do

There are lots of ways to improve basic climate knowledge and carbon numeracy. But we should focus on the arenas in which people’s knowledge gaps are the largest: What is climate change, and what are the best things to do to stop it? Upstream policy interventions are essential, but people need to understand the basics to care enough to advocate for those important interventions.

Quick Tips for Climate Shifts

The message isn’t austerity. It’s that we need to be smarter. “We don’t have to become calculators,” says Shahzeen Attari, an associate professor in the school of public and environmental affairs at Indiana University Bloomington. “We just need to know the most effective things we can do and go out and do them.”

We should be doing the things that get the most bang for our buck. Right now, we’re spending lots of effort on the wrong things. Simple heuristics or shortcuts can help people focus on the most important things to reduce their footprints, starting with how we travel, and moving on to how we power our homes and what we eat.

Label This

We should really slap carbon labels on everything. There’s no excuse for not providing people with what should be one of the most important metrics in determining what they buy. Recent polling by Canadian climate policy institute Clean Prosperity suggests 71% of Canadians would like to see these labels on their products. Another recent study by Globescan, a research consultancy, finds that people overwhelmingly want to live sustainable lifestyles but need concrete information to support their efforts.

As technology makes it easier and easier to calculate a product's emissions, the industry complaint that figuring out how to do this is untenable or expensive no longer holds water. Large manufactures manage every aspect of their supply chain. (It’s why they can do things like get rid of unsustainable suppliers, as the Mars candy company did with palm oil). Calculating emissions along the way is increasingly becoming the cost of doing business. A few big manufacturers, including Unilever, have already committed to doing so.

How companies label will also help people understand and quantify their emissions. Carbon Trust, a leading U.K. carbon footprint labeller suggests language like “this product is x times lower than the market standard.” Companies can also share emissions info by representing it with visual metaphor. For example, trying to visually quantify emissions in ways that people understand, such as traffic lights or a simple scale of 1-10. In this way, labels can fulfil their responsibility to disclose, while also helping improve carbon numeracy for consumers.

“I think we should label all the things we buy, so all consumer products going from a sandwich to a car to a flight we book,” says Zhao. “That doesn’t necessarily mean you can influence actions, but the hope is that consumers would become more aware and they will make different choices if they can.”

That said, Attari cautions that labels are not the only solution. “Given our limited time and attention, people need to know the things to do as individuals, and as political actors. That includes things like voting, protesting, and voting with your wallet.”

Put a Price on it

A partner recommendation to carbon labeling products is putting a price on carbon itself, in the form of a carbon tax. A carbon tax means the cost of the good or service will automatically reflect the emissions required to produce it. And in a world with far too much information to consume already, this seems the wisest, fairest, and easiest course of action. By pricing carbon, the cost of the good or service gives us important information about its emissions intensity. Together, labeling and taxing go a long way towards informing the consumer of the true cost of emissions. It’s about transparency and clarity. And you know, saving humanity.

Of course, we need a whole whack of other solutions, too. But to mobilize people in support of our most imminent existential threat, we should use the simplest, quickest tools to bring the world up to a modest degree of carbon fluency. There isn’t time for anything less.

This week

Thoughts on climate literacy? How important is it? LMK!

People dancing

Hope you are happy and healthy.

Have a wonderful weekend,

Sarah

PS. Does this newsletter go to your junk mail? Please drag it from promotions to your primary inbox!

PPS. Like this newsletter? Tell a friend?

PPPS. As always, lmk me how I can make it better! Is it too long? too first-persony? too momjeansy? I’d like to mix it up, so please share.