The weight of waste

Or, fight for your right to repair

I was baking up a storm and the storm smelled like plastic. Given my occasional absentmindedness, my husband looked for a scrap of stray packaging that might have affixed itself to one of my baking tins. But nope. It was then that we noticed the black smoke was coming from behind the clock. We quickly dragged the oven away from the wall and unplugged it before major tragedy occurred. Well, the half-baked chocolate peanut butter cakes were a major tragedy in some parts of our household.

Our stove is only two-and-a-half years old. It was bought after hours of reading reviews, checking reputable sites, and basically doing all the things most people do when weighing a large and flammable purchase. And yet, it’s a lemon. (Definition: A product that craps out within 5 years of purchase but outside of warranty) The cost of repair was more than half of the cost of the oven itself. And I will no longer fully trust it not to burn my house down.

But if I cut my losses and buy a new one, the landfill weight rests on me. Sure, some of the parts will be recycled, but the unusables will go to landfill and the carbon-heavy cost of manufacture and shipping will rest on my conscience. If we had real Extended Producer Responsibility, this would not happen. Producers would design for longevity, not wanting to shoulder the burdensome cost of taking care of the entire lifecycle of a product. It means the oven would have cost more when I bought it, but that price would be, ahem, baked in. All ovens would cost a few dollars more, fewer ovens would self-destruct. At least my oven was repairable. We know that so many of the goods made today are designed for obsolescence. I remember taking my Nespresso (don’t ask! We’ll do a coffee talk edition of MVP one day) to the repair shop about a decade ago. He told me he was unable to fix it because Nespresso used a proprietary screw system. Absolute manufacturer evil. And it’s only gotten worse since.

Despite pushback from some of the biggest companies in the world who see a threat to their business model (looking at you, Apple, as I type this on my Mac), the Right to Repair movement seems to be gaining some traction. It’s a push to allow consumers access to the parts and tools needed to fix their goods. It’s a push to give consumers the choice not to have to toss their appliances because producers have locked away the solutions that would enable reuse.

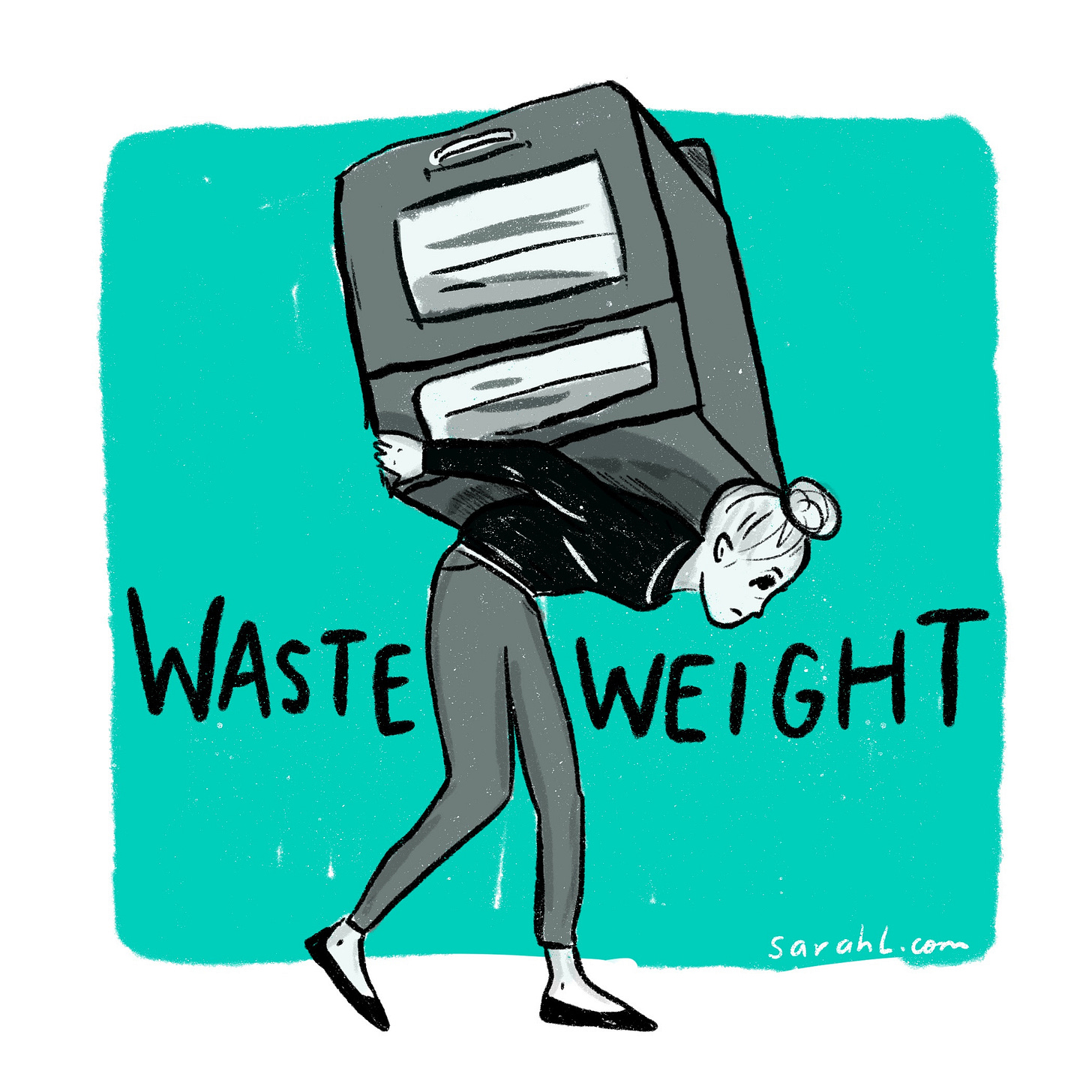

It’s very necessary. Because beyond the cost, time, and hassle it takes to attempt to fix our goods, the waste weight is too much to bear. And it’s a burden that should not rest on the shoulders of consumers alone. Sometimes I lie awake at night wondering how much of the Pacific Garbage Patch belongs to me. I feel guilty about the plastic salad clamshells and the overpackaged unnecessaries. And I feel angry about the stuff that I didn’t want to send away — the stuff that should have worked but didn’t, the things that ought to have been able to be fixed.

The way into this problem is both micro and macro. At the micro level, I’ll shake my fists at Frigidaire, demanding more and better, using whatever platform I can clamber onto to make them listen. At the macro, I’ve joined my city’s circular waste council. I’ve never been on a city committee before.