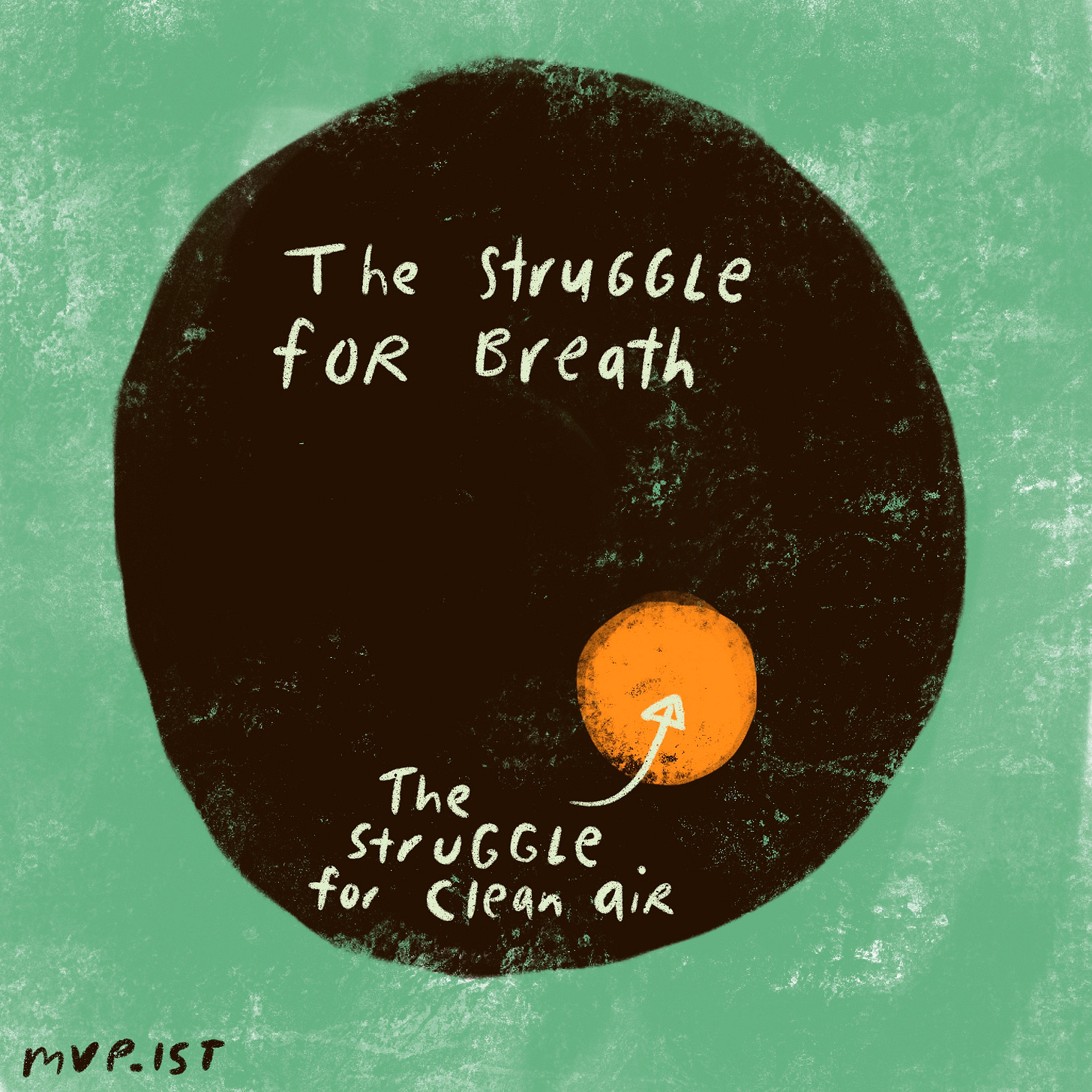

What Good is Clean Air if People Can't Breathe?

(No good)

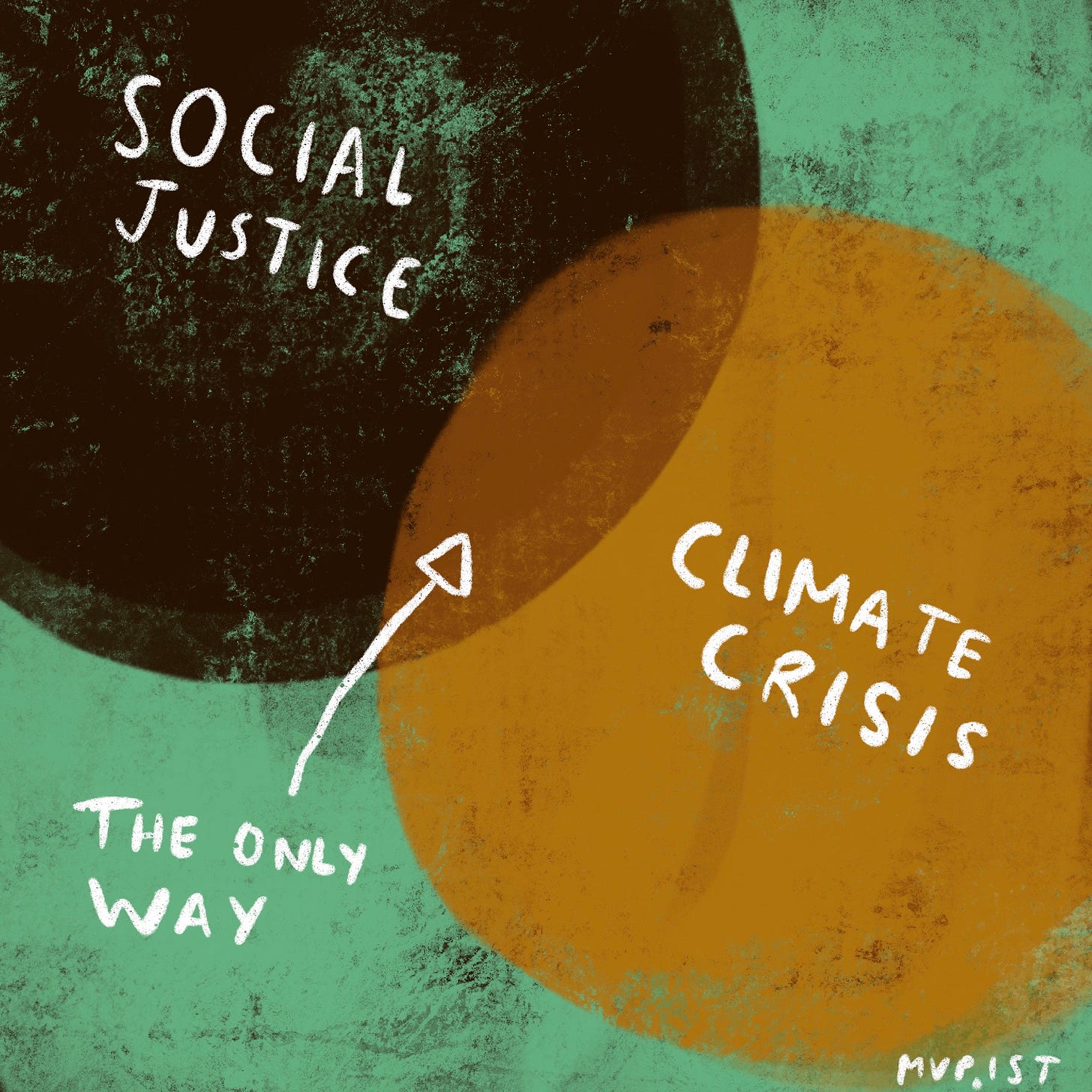

Climate change and racism are both systems-level problems. That sounds big, theoretical, and obvious. For most people, it doesn’t sound like an insult. But here’s another way to say it:

If I am not working to fight climate change, I am supporting climate change.

If I am not actively anti-racist, I am racist.

The thing about systems-level problems is that the system chooses a default side for you. When the system is destructive and you live in the system, you are destroying. It’s not your fault that you were born into a system; it is your fault if you recognize this and do nothing.

That’s not how I used to think. I used to think that there were good guys, bad guys, and everyone else. There were civil rights heroes, there were Ku Klux Klan bigots, and then the whole mushy middle of society, with me mushed in there with them, leaving the work to others so I could finger paint. Now, I know that’s wrong.

Now, I can explain the fearful unease I experienced while I was a student at Florida State University watching the ‘confederacy parade’ wend its way through campus. I always felt deeply uncomfortable in Tallahassee, a discomfort that rose to fever pitch on the day me and my friends came upon a group burning a cross at our favourite lake (!). We timidly crept back to our car. Two Jews, a Cuban, and a Black person, and we did nothing ... except make jokes about it for years thereafter. We didn’t talk about it seriously, and we certainly didn’t examine the social structures around us, or work toward change. We ate pizza.

Around the exact same time that I attended Florida State, writer Ibram X. Kendi was studying at FAMU, a historically black university in Tallahassee. All I knew of FAMU then was that they had amazing step dance teams and a fun marching band. I wish I had learned more. Kendi’s experience of Tallahassee was deeply unsettling and formative. He talks about the racism he experienced from the predominantly white FSU population and the Republican staffers that strolled the state capital’s sleepy streets. He grappled with the entrenched racism of his environs. FAMU was where Kendi began to wrestle with the ideas that he would shape into How to be an Antiracist. In this wonderful interview with Ezra Klein, Kendi unpacks the idea that racism is a fixed thing. We can, all of us, say or do racist things. And we can just as equally say or do antiracist things. But there’s no such thing as not racist. In moments where we do not actively speak out or act, we are racist, because our silence is a complicity that reinforces the way things are, which is, you guessed it, racist. For people who care about environmental work, the silence that has pervaded has actively reinforced the status quo, and in so doing excluded many Black people from participation. I find Kendi’s arguments not only deeply sensical, but gracious and warm, and human. And catnip for a policy wonk/systems change person. We are the products of systems. We must work to change them. If you listen to one thing, I suggest you make it this far-ranging conversation.

How many times in my life have I witnessed injustice, either actively or passively, and not acted? So much of the well-meaning education I was given focused on the clear acts of evil. This oft-quoted Martin Niemöller poem has been in my brain since I was 15. But its drama speaks to epic choices. Kendi’s framing is all at once more clear and more practicably actionable. Whenever you’re not making the right choice, you’re making the wrong choice. It’s tough, but not nearly as tough as the struggles others have endured for hundreds of years.

I remember being shocked when I first read about the racism of some of the foundational conservationists that Marjory Stoneman Douglas so ably took down. I really shouldn’t have been. Racism is, of course, inherent to the environmental movement because it’s inherent to everything. And the idea that we can fix one problem without fixing the other is single-minded at best and willfully obstructionist at worst. My fixity on parts per million has often precluded me from thinking about the whole ecosystem.

The availability bias makes us grab onto what’s nearest to us and think things are a certain way. It’s why filter bubbles are so dangerous. What’s around us is representative to us (hello #representationmatters). I am conscious of the fact that what’s around me is not indicative of what’s going on way over on the other side, but I have been less conscious of the fact that my bubble is a very particular subset of the green left. Sometimes, indications that we are not all the same shade of seafoam seep into my view.

This note at the bottom of 350.org’s solidarity letter really jumped out at me:

PS -- We understand some of you on our email list may be confused about why a climate change organization is sending an email about racial justice. Every time we send these kinds of emails, we get messages asking us exactly that, so we'd ask in this moment that you join us in reflecting on these connections. You can start by reading our blog reflecting on how opposing white supremacy and addressing anti-racism is climate justice work.

I think the note made me realize (even more than a million police offers with clubs) just how much further we have to go. It is daunting but we can grow stronger knowing these conversations about racism and environmentalism are finally happening. Yes, things are horrible. Yes, let’s fix them.

Many much more knowledgeable people have shared wonderful lists, tools, resources, and ways to learn. At the bottom of this newsletter are things that I have found deeply helpful and beautiful.

THIS WEEK

What are you unpacking? What are you learning? What are your thoughts? LMK

I will no doubt get a ton wrong, as I have time and time again, so PLEASE feel free to tell me as much.

LAST WEEK

Green only for some. Really good piece on how green space is inaccessible for many in Toronto.

CUTE PEOPLE DANCING

Imagine dancing this well while playing an instrument and marching across a field in complex formation in 100 degree heat!

I hope you are healthy and safe and learning,

Sarah

IT’S WORK. IT’S UNCOMFORTABLE. LET’S DO IT.

So many great pieces by Rachel Elizabeth Cargle.

What is intersectionality? Here’s a really good explainer from Yes!

It simply does not make sense for anyone in the environmental or climate movement to stay silent on systemic racism. The burden of the issues that you’re working on are falling harder on all people color, and particularly Black people. Unless you’re willing to solve the roots of that disproportionate impact, you’re not solving anything at all.

- Liz Havsted, ED of Hip Hop Caucus, speaking to Emily Atkin, in Heated.

There is a habit in too much of the environmental movement, I fear, of talking about politics in a way which avoids questions of power, which fails to actively stand in solidarity with the marginalised. This isn't because these environmentalists intend to oppress, but because messages which don't confront power are promoted by the powerful. Messages which do challenge are made controversial, and attacked. And so life is easier if you never confront those who are actually most able to change things. But you don't make any difference in the world by having an easy life, and unless we actively avoid the traps laid by oppressive systems we will inevitably fall into them. All of this has long been understood by the environmental justice movement, the climate justice movement, movements against environmental racism and in solidarity with indigenous people, eco-feminist movements and many more besides.

- My Environmentalism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit. (Adam Ramsay in Open democracy)

In our emergency times of disastrous environmental transformation, it is urgent to bridge aesthetics and politics, expanding consideration of these entanglements in ways that challenge white supremacy, the militarization of everyday life, creeping fascism, and apocalyptic populism, as well as mass extinction, fast and slow environmental violence, and extractive capital. These are the central ingredients of socioecological climates that differentially impact being and define the uneven exposure to toxicity, violence, and death.

For basically all of history, our Black friends, Black family members and Black people who we don’t even know have borne the burden of proving their humanity. We have overwhelmingly allowed Black people to do the work of dismantling white supremacy—and then we have characterized their work as distasteful and overreaching, whether that is Colin Kaepernick kneeling during the national anthem or the Minneapolis residents literally risking their lives to protest. (It’s still a pandemic, remember.) This is not to discount the work that non-Black people of colour, Indigenous people and white people have done to build a more equitable society, but it is to state clearly that we still have more work to do, both publicly and privately, to unlearn anti-Blackness.

- Stacy Lee Kong This is such a great and thorough list (Friday Things)

Together, let’s interrupt cycles of violence and hate, and harness the courage and imagination necessary to enact change. The time for small and large scale shifts is now.

This is a really good piece on Anti-Racist parenting. (Yes! Magazine)

Meanwhile in Canada, things are not so great! (Maclean’s)

This video, shared by my friend Hannah, is a really fantastic primer on how to be a helpful human when responding to racist attacks. (Also, read Hannah’s newsletter this week!)

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me was one of the best books I’ve ever read. His talk with Ezra Klein, Ta-Nehisi Coates is Not Here to Comfort You, from a year ago is fantastic. I’m looking forward to listening to a new conversation they had a few days ago. I think you’ll like the name: Why Ta-Nehisi Coates is Hopeful.

And finally, I’m a huge fan of Leah Thomas. Read her, follow her, share her.